Happy New Year everyone! Even though we’ve left 2020 behind, COVID-19 is still very much with us and there have been some developments in the UK for the past few weeks that are making headlines. So for the first post of the year, let’s dig into the state of the UK.

SARS-CoV-2 Variant B.1.1.7 or the UK Variant

First off, I want to clarify the difference between a strain and a variant as a lot of people use these interchangeably but they have very specific meanings when used technically. Differences between strains are large enough that they have different proteins on their surfaces, think of influenza viruses where we differentiate strains by the surface markers H1N1 from the Spanish Flu in 1918 and Swine flu in 2009 or H7N9 from 2018 . Variants are viruses with smaller differences than strains. While there are mutations present between variants there has to be a functional difference to be recognized as a different virus strain. Currently, the UK is dealing with a unique variant of the SARS-CoV-2 strain of coronavirus.

So what’s actually different about the UK Variant? This particular variant is being defined by a set of 23 mutations that occurred in the virus [link]. Specifically, 9 of the mutations are present within the spike protein including the D614G mutation that has been found to increase infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in animal models [link]. While the D614G mutation did not significantly change the spread of COVID-19, it was able to become the dominant strain where it was present due to a better ability to bind with cells. The combination of mutants is not surprising, but together they can have a greater impact than the sum of each individual mutation.

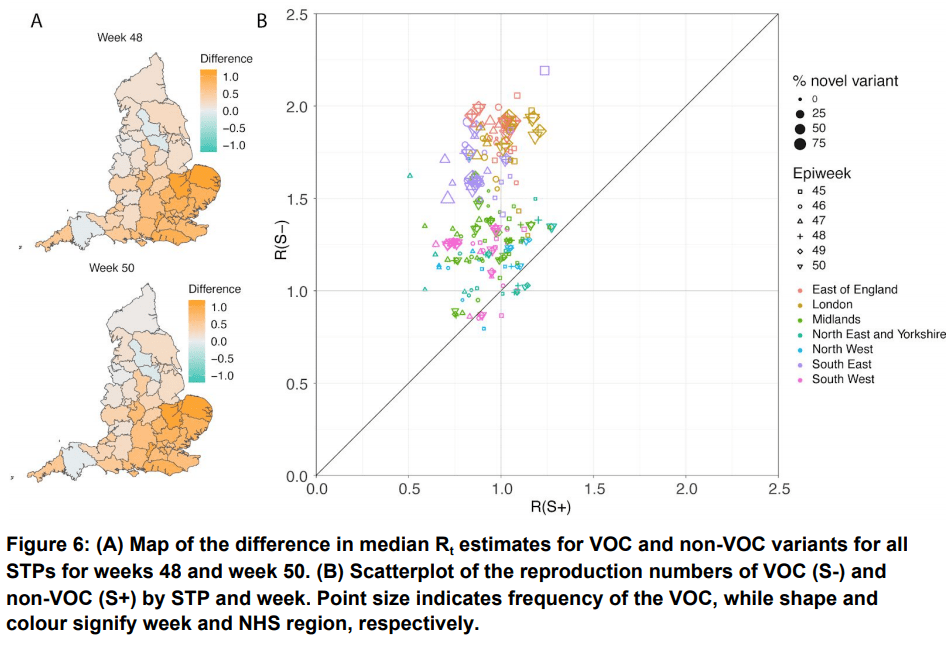

While there is no current data that proves B.1.1.7 is able to infect people better, it is definitely correlated with the rise of cases in southeast England [link]. Current estimates say that the new variant may be as much as 70% more transmissible, meaning that if you were exposed to one of the original COVID-19 variants and had a 50% chance of getting sick then there is now up to a 85% chance you could get sick [link]. (Just FYI, we don’t really know the chances of getting COVID-19 after exposure, 50% is used as an example)

The good news is that the new variant does not appear to be associated with any increase in disease severity, so while more people may get sick they won’t be any more at risk because they have this COVID-19 variant over any other one. Additionally, while there are multiple mutations in the spike protein for this variant, it should still be compatible with current vaccines. That being said, if a new vaccine with these specific mutations became necessary, BioNTech says that it will take them just 6 weeks to have an updated vaccine ready for testing [link].

What is currently under question are current antibody treatments, as they tend to only target a specific location on the spike protein. If the targeted location is mutated, then the antibody therapy won’t work anymore. Monoclonal antibodies are more likely to have targeting issues since they only have 1 target while polyclonal antibodies can have multiple targets. There’s no current data on if there is a change but with every accumulated mutation it becomes an increasing possibility that antibody therapies may have limited efficacy [link].

We know that this variant has now spread outside of the UK and is present in many countries around the world including the US [link]. With time and sequencing data, we will see if this variant spreads as fast in other countries or if there could be other reasons for its sudden rise in the UK. Sadly, the US is not sequencing a lot of COVID-19 samples so we may be able to get a nationwide idea of the spread of this or any other variant.

UK Approval of AstraZeneca Vaccine

As of December 30th, 2020 the UK authorized the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine for use as an emergency supply. the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which is a parallel to the US FDA, has authorized immunizations of individuals 18 years or older with two doses administered with an interval of between 4 and 12 weeks. While this is a great step forward, one major piece of the decision is missing…

There has been no public release of late phase clinical trial data.

Let me say that a different way, we have no way to independently verify the safety and efficacy of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. As no data is currently published or released outside of a publication of intermediate results in the Lancet [link] in a study that had large flaws including but not limited to vaccine dosing and dose spacing. Additionally, the Lancet study pools the results of people that had very different experiences with the vaccine by including people in a Brazilian study which used only a single dose while also including people who received two doses. Normally, these are kept as separate populations as we would expect different results from people who got one dose of vaccine vs two [link].

The inconsistencies of dosing amounts can have a large impact on how well the vaccine works, and the AZ Lancet study has a flaw where a small subset of people received half a dose with their first shot and a full dose with their second. This subset, of low number and limited age, showed a better response than the subjects who received two full doses of the vaccine. BUT that could be because people older than 55 were excluded from the subset and tended to have lower responses to the vaccine meaning that the change in efficacy could be due to subject age rather than dosing. This dose response is something that needs to be further looked into, but with the vaccine already being authorized in the UK and India the appropriate studies may never be performed.

Another strategy the UK is using to help create herd immunity is separating the two vaccine doses 12 weeks apart, as opposed to the Pfizer 3 week and Moderna 4 week dosing regimen. The idea is that there is some level of protection generated with the first vaccine so the more people who receive at least one dose the higher overall level of resistance there could be. The downside to this is that by combining a possibly low efficiency vaccine, somewhere between maybe 32-82% effective and even the the range of that number is problematic on its own, with a rapidly spreading SARS-CoV-2 variant there could be a lot of people overconfident in their level of protection after the first dose that turn into drivers of the pandemic rather than the resistant population we are hoping for.

For these reasons, I don’t expect the AstraZeneca vaccine to be approved of the in the USA anytime soon. It seems that AstraZeneca knows this as well as they have yet to even file with the FDA to try to apply for emergency use authorization (EUA). While the released data shows some interesting numbers, there needs to be more clear, consistent data in my opinion before we will see a USA release of the vaccine. There may be data that was made available to the MHRA but until that information sees wider release, I wish the UK all the luck because it seems that luck is what the AstraZeneca vaccine depends on.

Welcome to 2021; may it be better than the last year,

-Your friendly neighborhood scientist