Now that vaccine rollouts are happening across the world, we’re starting to see a real impact in the daily case and hospitalization numbers for countries leading vaccination efforts such as the UK, Israel, and the USA. In the meantime, other countries such as Turkey, India, and France are still seeing large numbers of daily cases and variants have been detected and shared all over the world. Additionally, as of May 10th, 2021 both the USA and Canada are allowing the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to be given to kids 12 and up which will help shut down one of the current drivers of the pandemic in those countries. Yes, unsurprisingly kids while not strongly affected by COVID-19 can still bring it home. [link]

With all of that brewing, some people are seeing friends for the first time in months while others are trying to figure out what the rest of the year is going to look like. There’s a lot of uncertainty going on, and I’d like to help put some of that to rest and let people sleep a little easier with some good news.

Vaccines vs Variants

Variants keep popping up, with the B.1.1.7 (UK) and B.1.351 (South Africa) becoming the dominant SARS-CoV-2 types in many locations across the world. These variants appear to be better spreading and carry a possible risk of more severe disease and higher death tolls which are causing higher numbers of COVID-19 cases around the world. Currently, a major key to our fight against COVID-19 is dependent on abundant use of the available vaccines from companies such as Moderna, Pfizer, J&J, and AstraZeneca.

All of the above listed vaccines and others were developed from the original strain which had the genomic sequence released in early 2020 [link, link]. Quick highlight that we got this in-depth data only number of months after the first cases of COVID-19 began occurring, a speed which went from being science fiction to science reality in a startling short amount of time. While we are getting new SARS-CoV-2 variants all the time due to random mutations as the virus spreads, only a few of the variants, such as those stated earlier, seem to have an impact on the outcomes for the people infected. These random mutations can occur throughout the entire viral genome, but really matter to vaccines when they occur on the vaccine target which is the Spike protein.

The spike protein is what the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to get into cells and cause COVID-19. By using vaccines to target the spike protein, we’re able to train the body to attack the virus in such a way that antibodies can block the virus from entering the cell – these are known as neutralizing antibodies. Antibodies are dependent on the right shape or sequence for them to bind to, when mutations occur that shape and sequence can be altered.

To date there has been a limited amount of tests performed to measure the body’s response to the variants. Most of the studies so far have been performed in test tubes and aren’t exactly reflective of what really happens in the body which means that we’re not seeing the whole picture of how well our current vaccines can protect us from variants. Studies that show a dramatic decrease in vaccine’s efficacy against variants test a variant, or even just a variant’s version of the spike, in a lab against antibodies harvested from a person react to the spike protein. From these tests we get big dramatic headlines of doom and gloom that pronounce the variants are escaping the vaccine. The truth is that there’s a whole adaptive immune system which includes a bunch of different cell types that become trained after vaccination and work to recognize and attack diseases during infections. Because of this difficult to measure whole body response, real world data is a much better determinant of vaccine efficacy against variants.

Real World Data

Now, COVID-19 is still a recent disease with only world wide prevalence for a little over 1 year it’s still hard to get thorough studies together with real world data. At this point we’re able to look at a few key locations and see what’s happening there.

Israel – There has been an incredible vaccination effort in Israel which resulted in a majority of the population being fully vaccinated, providing an incredible testing ground to see how the variants are spreading. A publication still in pre-print and available on medrxiv studied what strains were occurring in their vaccinated population and pair matched participants to non-vaccinated people. This study found first that B.1.1.7 was quickly becoming the predominant variant in Israel, which makes sense as it is capable of spreading better than the original virus. Next, the study found that people who had only received one dose were more likely to have the B.1.351 variant than unvaccinated people and further they found that even people with two shots were more likely to have the B.1.1.7 variant. This data shows strong evidence that the vaccines do protect against SARS-CoV-2 very well, and a bit less when compared to the newer variants that arose last year. What this doesn’t tell us is the efficacy of the vaccine as we don’t know how many people were totally protected from the variants due to their vaccination status. [link]

South Africa – Pfizer and BioNTech have stayed busy running clinical trials across the world to continue to make their vaccine available in more places. Valuable information was released in a press release on April 1st from the ongoing Phase 3 clinical trial in South Africa. While it is disappointing to see a press release and not a full scientific publication, if the numbers are even close to what Pfizer is currently claiming then there’s good reason to hope we won’t need new vaccines for every variant as it pops up. In fact, B.1.351 doesn’t seem able to escape the Pfizer vaccine as they report a 100% efficacy in a region where that variant is the predominant strain. Even in the presence of a few mutations within the spike protein, the variant is still close enough to the vaccines that vaccines are proving highly effective. [link]

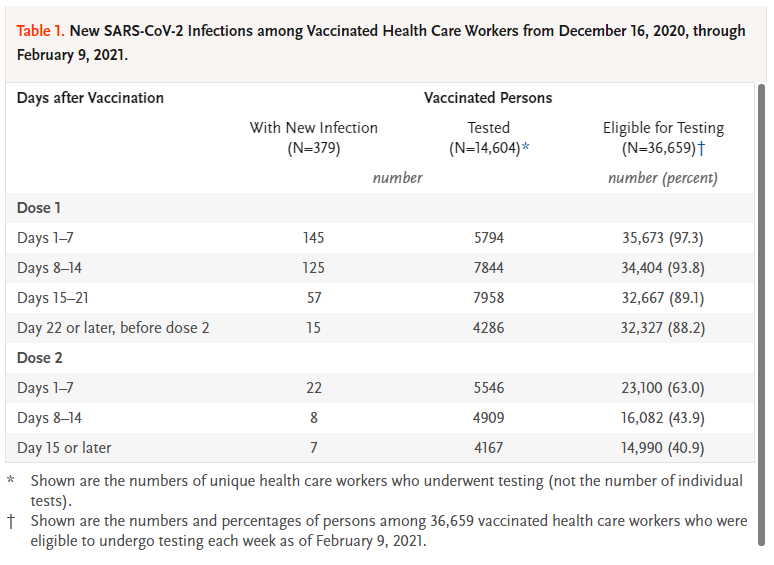

USA – One final study I want to bring up was performed in health care workers in California at two sites. This study tracked how many of the workers who received their vaccines contracted COVID-19, which is especially important considering that these are the people who have the highest exposure because they could be working with the sickest cases within a location that is full of sick people. The numbers are staggering with 36,659 people receiving at least one vaccine with 77% coming back to receive their second shot. The data was tracked by weeks after dose and each week the number of people who had SARS-CoV-2 detected in their system just plummet. Overall it was found that only around 1% of people who received a vaccine were diagnosed COVID-19 with very, very few (0.17%) getting sick 15 days after their second dose. While none of the variants were tracked during this study, it seems that even people at high risk are extremely well protected. [link]

Vaccines Going Forwards

With all this data taken in stride, it is my humble opinion that we’re not at the point yet where we will need a shot specifically for any of the current variants. While much buzz has been made about the E484K mutation [link], ironically dubbed the “eek mutant”, possibly being a route of vaccine escape there are no current studies to back that hypothesis with real world data. It’s still possible that the E484K mutation may be the first step on a path to full vaccine escape but it could take time before the right mutations occur at the right places. SARS-CoV-2 is not an especially fast mutating virus so there’s a chance we still have time to get the pandemic under control before a true escape variant becomes reality.

Until we see real world loss of efficacy, there’s no reason to think that we’ll need to get even more shots for the variants. Follow ups from the original trials are still being done though to help determine just how long the protection from the vaccine lasts. The flu shot is the only typical vaccine we receive annually and that’s because of just how many strains there are of flu. Maybe one day we’ll have a universal flu vaccine, but in the meantime we’ll have to make due with our annual vaccine. Early theories about COVID-19 spread and evolution led us to believe that we might need a yearly COVID-19 vaccine, the data showing that the current vaccine covers variants really well means it may be on a schedule with wider spacing like a TDaP vaccine where we receive it regularly at wide intervals.

The main thing that needs to happen for us to not need an annual shot is to continue preventing the spread of COVID-19 by continuing our mask wearing, social distancing, and hand washing behaviors. These things combined with vaccination across the world will be they key to turning COVID-19 into a controlled illness from its current pandemic state. If we ignore the tools we have that work, this disease could very well turn into a never ending battle for our healthcare systems, which is the last thing we want.

Stay vigilant; we’re in the endgame now,

-Your friendly neighborhood scientist